These intricate art forms once flourished across India's diverse landscapes. Today, they teeter on the edge of extinction—but their revival is in our hands

In the race towards mass production and digital design, the soul of handmade India is gradually fading away. Across villages and hill towns, six exquisite art forms—rooted in philosophy, folklore, and ritual—are disappearing into memory.

Crafted over centuries by artisans whose skills were often passed from mother to daughter and father to son, these endangered legacies are more than mere decorative objects. They are living testaments to India's rich cultural heritage.

Once patronised by the Bahmani sultans in 14th-century Bidar, Karnataka, Bidriware is a delicate inlay craft that marries blackened white brass with pure silver. Developed by Persian artisans invited by Indian royals, Bidriware evolved into a fusion of Persian elegance and Deccan aesthetics. Craftsmen etch intricate motifs onto metal, often featuring floral or geometric designs, and embed silver wire into the grooves.

The final transformation? The object is dipped in a solution made from the soil of Bidar fort, a soil untouched by sunlight for years. It is this secret that gives the piece its iconic black sheen.

Originating from Karnataka, Kasuti embroidery is a geometric, thread-counted technique executed entirely by hand. Practised by women since the Chalukya era, its name derives from 'kai' (hand) and 'suti' (cotton). Every stitch exhibits mathematical precision—no knots, no freehand.

Traditional motifs include gopurams, lamps, palanquins, and chariots. A Kasuti saree wasn't just festive attire—it was a rite of passage, a wedding heirloom, a silent testament to patience and skill.

Among the Toda tribes of Tamil Nadu, embroidery isn't just a hobby—it is a heritage. Toda women craft their signature red-and-black patterns on white cloaks known as "pootkhul." These symmetrical motifs, stitched without backings or knots, are deeply symbolic of buffalo herding, nature, and tribal myths.

(Credit: Isha Foundation)

Both sides of the fabric are equally finished. To wear one is not merely to adorn art, but to carry a story of a vanishing people.

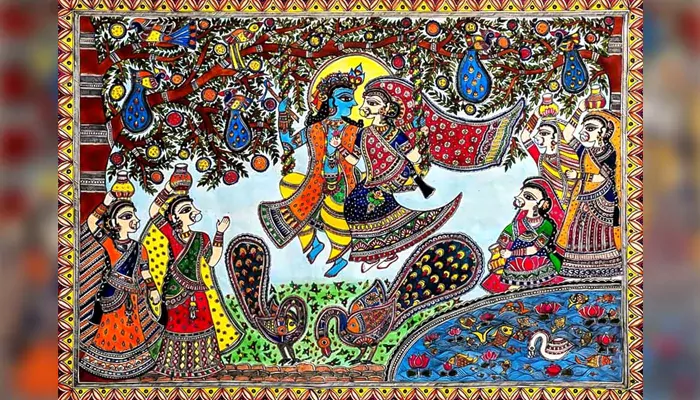

Hailing from the Mithila region of Bihar, Madhubani art once decorated the mud walls of homes. Today, it persists on canvas and paper, still reflecting the same ritualistic motifs: gods, animals, celestial bodies, and marriage scenes.

(Credit: Cottage9)

Painted using twigs, fingers, and matchsticks, the colours are derived from turmeric, indigo, soot, and rice paste. Not a single inch remains unfilled. Every curve and line embodies faith, especially that of women, who have passed this art through generations.

In Molela village near Rajasthan's Nathdwara, artisans carve flat clay plaques depicting tribal gods, village scenes, and sacred rituals. This tradition, over 800 years old, originated when a blind potter had a dream of God Dharamraja and awoke healed.

These terracotta icons are still transported across states by Bhil and Garasia tribes, who place them in shrines to ward off illness and misfortune.

The art form, once deeply spiritual, is now being reimagined for contemporary walls.

From Gujarat's Sankheda village comes this vibrantly coloured teakwood furniture, lacquered in deep maroons and golds. Used in weddings and royal courts since the 17th century, the designs are etched by hand, painted with tin foil patterns, and sealed under polished lacquer.

Once gifted as symbols of auspiciousness and legacy, Sankheda pieces are now rarely seen beyond archives and elite homes. Its survival depends on adapting to modern interiors, without losing its ornate essence.